Tarantula Tracking with Dr. Shillington

.jpg)

Description: Dr. Cara Shillington with an antenna, tracking a radio tagged tarantula. This Article Includes a Photo Gallery by Sue Keefer.

BY SUE KEEFER

Tarantula Tracking with Dr. Shillington

Sunset, moonrise, a backpack full of tarantulas—what more could a nature writer and photographer ask for when accompanying a tarantula researcher out to Comanche National Grassland?

Steve and I had the pleasure of following Dr. Cara Shillington around her research plot on a recent evening. Cara is a professor of biology at Eastern Michigan University. Her area of expertise is the natural history of tarantulas, especially behaviorial and physiological ecology. Readers may remember previous SECO News articles about graduate students Dallas Haselhuhn and Bradley Allendorfer. They were Cara’s students.

Although Cara had been out to the Grassland with students previously, she was only able to stay a few days. This year, however, she took a sabbatical from the university and is here doing her own tarantula research here for about three months.

.jpg)

Tarantula on the road on the way to the research site, just before sunset.

Tarantulas haven’t been studied nearly as much as other animals, such as mammals and birds. For one thing, depending on your perspective, they lack the “cute” factor. Much of the current research on tarantulas has been done by Cara, her students, and a few other tarantula experts.

Perhaps I should explain about the tarantulas in the backpack. Cara had captured nine male tarantulas the previous night that were wandering around on the prairie. Each tarantula was in its own plastic, lidded container. When out of the field, she placed “Bee markers” on each tarantula. These are tiny tags with numbers on them. They’re called bee markers because beekeepers use them to put on their queen bees, but they also work well on tarantulas. They come in assorted colors, with 100 markers per color. She’s on her second set of bee markers, so that should give an idea of how many tarantulas she has marked so far.

.jpg)

A tarantula in infrared light, which is sometimes easier to use at night than white light.

She’s found that once the marked tarantulas are released, most tend to find a burrow and spend a few nights in one before they start wandering again. She’s not sure how long they spend in a burrow. A couple of nights ago, she found one in a burrow that she hadn’t seen since she released it Sept. 5.

Some of the male tarantulas also have tiny radio tags, which are placed on the tarantula's cephalothorax. Cara is able to track them by using a portable antenna. The transmitters emit a small beep, which enables her to find the spiders. However, if the spider is a burrow, it’s harder to locate because of how the sound carries. She marks one that she finds with a flag, but since they change locations frequently, she pulls up the flags when they move. Unfortunately, she recently found one of the radio tagged males that had a punctured abdomen and died shortly after she found him. She’s not sure how the abdomen was punctured. Also recently, she lost track of a radio tagged male that had been sitting in a burrow for five days. She can’t pick up his signal. There are currently two radio tagged males out. One is actively moving around, but had moved into a new burrow, and the other one has been sitting in the same burrow for five days. She’s planning on tagging more in a few weeks. She wonders if radio tracking impacts behavior, but that would be hard to tell.

.jpg)

Note the tiny yellow radio tag on the cephalothorax, the light tan part of the body.

Cara uses different colors of flags as markers. One color indicates an occupied burrow, while another color indicates how far a tarantula has wandered from its burrow. She’s looking to see if there’s a correlation with how far they come out and temperature, as well as individual personality or age/size or body condition/nutrient intake. While we were there, she picked up a tarantula close to its burrow, weighed it, noted its body condition, and measured its abdomen, which is the only body part that changes size. This one weighed nine grams, which is within the range that females usually weigh. Males usually weigh five to six grams. Males can weigh up to eight grams, but that’s unusual. She carefully placed the female back in her burrow.

While we were looking for tarantulas, we also found several beetles and a large number of wolf spiders, including one that was about the size of a small tarantula we also saw. They have burrows in the same area as the tarantula burrows, and cross paths with the wandering tarantulas with seemingly no issues, although some may be tarantula food.

It should be noted that female tarantulas spend most of their lives in their burrows, venturing out only to eat. This time of year, the males, who may have been inside burrows for several years, start coming out to find females to mate with. Although this has been called a “migration,” it’s not. People might see the males crossing roadways and assume they’re going a long distance. However, they’re just looking for females. At this stage in their lives, the males have one purpose: to mate. Once they mate, if the female doesn’t eat them, they will die shortly afterwards. Even those who can’t find a receptive female will die.

If you see a tarantula, photograph it (safely—please don’t block roadways!), but otherwise please leave it alone. The ones that are seen out and about are males. They need to be left so that they can fulfill their purpose so that more tarantulas will be born. At any rate, they will die soon after they’re taken. There’s no way to tell if they have mated or not.

Also please stay away from the research areas that currently have colored flags.

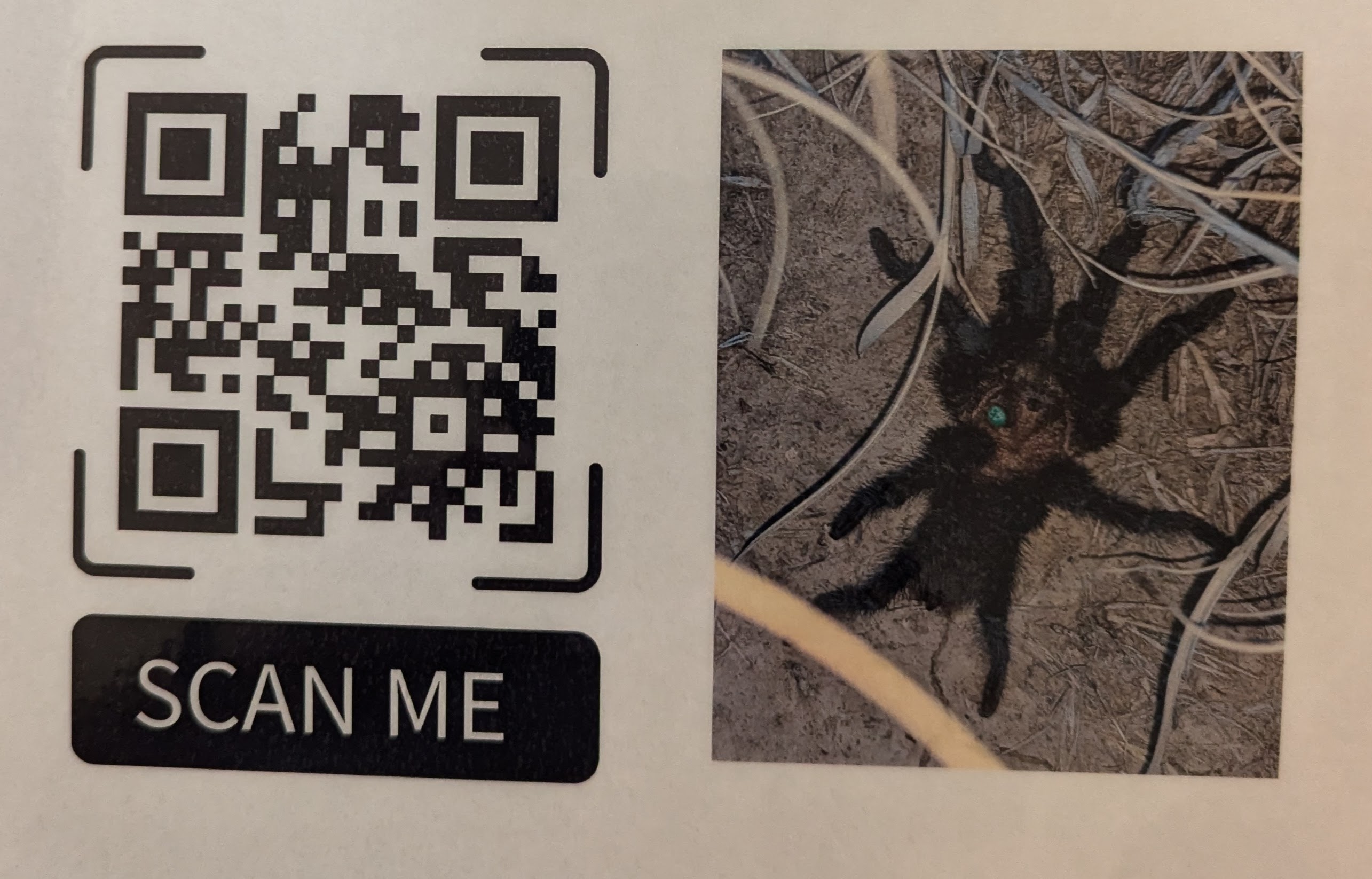

Use this QR code to enter information on a Google form if you spot a tagged tarantula like the one in the photo.

Should you see a tarantula with a colored marker on its back, please help research by scanning the QR code shown here (or click here) to access a Google form. You can add information such as the number on the tag and when and where you found the tarantula. It's okay to photograph it, but please don't otherwise disturb it. There are also posters with the QR code on them posted in La Junta and on the Grassland.

Cara will be giving a talk on her experiences tracking tarantulas at 1 p.m. Friday, Sept. 27, at the Learning Commons of Otero College. Dr. Paula Cushing of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science will be returning to talk about her work with spiders during the same time. Friday is the first day of La Junta’s Tarantula Fest. Here’s more information on the fest, including the schedule: https://visitlajunta.net/la-junta-tarantula-fest/

Related Content:

http://seconews.org/TakeAPhotoNotATarantula

Watch the Field Expedition Videos:

A Tarantula Field Expedition with Bradley

A Tarantula Field Expedition with Dallas

The A.R.T. Project 2024 - Sept. 28 - 29

Follow SECO News on Facebook.

Subscribe to the SECO News YouTube Channel.

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)